This is a story of love, lust, envy, greed, social climbing, back-stabbing, manipulation, and revolution! This is the story of the Affair of the Diamond Necklace, and although it has been told and retold through film, memoir, books, articles, online encyclopaedias, historians and more, the story is so fascinating we must retell it once again, with a Rocks & Co lens!

Madame du Barry by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1781- source: wikpedia

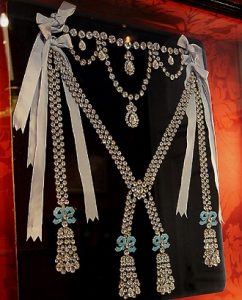

The ‘diamond necklace affair’ was a public scandal in the 1780s France, that involved the theft of an extremely valuable piece of jewellery. The diamond necklace at the centre of this affair was made by Parisian jewellers Boehmer and Bassenge and contained 647 flawless diamonds, with some at several carats each. This necklace was the most expensive piece of jewellery in France and possibly the world, at the time. Conservative estimates valued it at 1.5 million livres . The necklace was stolen in 1785 as part of a confidence trick involving Catholic Cardinal Louis de Rohan and several other figures. The story of this scam was later revealed in a public trial. Those involved in the theft of the necklace had used Marie Antoinette’s name as part of their swindle. Despite not being directly involved, the queen was publicly discredited by the diamond necklace affair, furthering the destabilisation that led to the French revolution against the Bourbon Monarchy.

The diamond necklace was commissioned by Louis XV for his mistress, Madame du Barry – sadly, the king died a year later of smallpox, long before the necklace was completed or paid for, practically bankrupting its creators.

Boehmer and Bassenge were eager to sell the finished necklace – but its extraordinary cost meant Royals were the only potential buyers. In 1778 the jewellers made an formal approach to Louis XVI, offering him the necklace as a possible gift for his queen, Marie Antoinette. The queen was shown the necklace, expressed some interest – however, the sale was not completed. According to legend, it was vetoed by Antoinette, who decided that perhaps battleships would be a wiser purchase for France! Boehmer and Bassenge were left to sell the necklace to royal families and wealthy nobles outside of the country, with no luck.

In March 1784 Jeanne de la Motte, the young wife of a con-man and a formidable adventuress and con-woman herself, began communicating with a high-ranking clergyman and diplomat Cardinal de Rohan, some say taking him as a lover. Rohan had fallen from favour with the queen, which was a great stumbling block to his political ambitions. Within a few months, Jeanne had convinced Rohan that she was a confidant and agent for Marie Antoinette. The cardinal began a lengthy correspondence with “Antoinette”, expressing his loyalty and devotion to her. Rohan received affectionate replies from “Her Majesty”, though these replies were forgeries written by Jeanne or her husband. The ploy was so effective, however, that Rohan came to believe that Antoinette was in love with him. He urged Jeanne to arrange a secret meeting with “the queen”. Jeanne organised a nighttime rendezvous between Rohan and a Parisian prostitute who looked close enough to the Queen of France, to fool him.

Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy, “Comtesse de la Motte”-source: Wikipedia

Fortified with large amounts of money borrowed from Cardinal Rohan, Jeanne de la Motte became a regular in high society.

The wickedly brilliant Jeanne was so convincing, many others in court came to believe that she was a confidante of the queen – among them the Parisian jewellers Boehmer and Bassenge. In late 1784 they approached Jeanne and asked if she could persuade Antoinette to purchase the diamond necklace. Jeanne and her husband found this opportunity too good to resist. Using forged papers, Jeanne convinced Cardinal de Rohan to acquire the necklace on Antoinette’s behalf. The 1.6 million livres fee, these papers claimed, would be paid in instalments. In February 1785 the necklace was passed to Cardinal de Rohan, who handed it to a third party purporting to represent the queen. The necklace immediately disappeared and was never seen intact again. It was broken up and its gold and diamonds were sold in the black markets of Paris and London.

Cardinal de Rohan -source: Wikipedia

The scam was uncovered several weeks later, when one of the jewellers asked a royal chambermaid if Antoinette was yet to wear the necklace in public.

An investigation soon uncovered the involvement of Jeanne de la Motte and Cardinal de Rohan. Both were arrested in August 1785, Rohan as he was about to conduct mass at Versailles. They were tried before the Paris parlement the following spring. The trial caused a sensation in the capital, with its chain of lies, forgeries, secret letters, prostitutes, nighttime meetings and Rohan’s deluded love for the queen – not to mention the missing 1.6 million livre necklace. On 31 May 1786. Jeanne de la Motte was condemned to be whipped, branded with a V (for voleuse, “thief”) on each shoulder, and sent to life imprisonment in the prostitutes’ prison at the Salpêtrière. In June of the following year, she escaped from prison disguised as a boy. Meanwhile, her husband was tried in absentia and condemned to be a galley slave. Cardinal de Rohan was acquitted, despite the weight of evidence against him and despite his sizeable role in the whole affair.

Most historians believe Marie Antoinette played little or no part in the ‘diamond necklace affair’. There was no evidence that she had communicated with – or even heard of – Jeanne de la Motte.

If anything both Louis XVI and Antoinette had acted with caution and responsibility by deciding not to buy the necklace which would have cast the nation further into debt. But in a climate poisoned by libelles, political pornography, and anti-royal gossip, many Parisians preferred to think the queen a willing player in the necklace fiasco. They interpreted the outcome of the trial as a cover up, a verdict engineered to protect the queen’s reputation. They chose to interpret the parlement’s acquittal of Rohan as a sign he had been ‘used’ or betrayed by Antoinette. In the poisoned environment of 1780s Paris, it was more convenient to think Marie Antoinette guilty of conspiracy, even if the evidence contradicted this.

Marie-Antoinette, painting by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, 18th century; in the Versailles Museum

“The Queen’s necklace”, reconstruction, Château de Breteuil, France

Diamonds, Gold, Passion! Come on over to the Rocks &Co. for more…

photo credit: “The Queen’s necklace”, reconstruction, Château de Breteuil, France

Historical references: Alpha History.com, Wikipedia