The Cheapside Hoard story may be old news to some but it is of such importance and value, it is worth a re-visit.

An incredible collection of jewels, discovered by chance in 1912 after centuries of concealment, are in the collection of the Museum of London. Nearly 500 pieces, including jewellery, loose gems, and functional items, offer a unique glimpse into the global trade and use of gems in the 16th and early 17th centuries. If you are a jewellery aficionado this collection a must see.

The Cheapside Hoard gemstones were sourced from across South America, Asia and Europe. The gems used included: emerald from Colombia, topaz and amazonite from Brazil; spinel, iolite, and chrysoberyl from Sri Lanka, Indian diamond, Burmese ruby, Afghan lapis lazuli, Persian turquoise, pearls from Bahrain, peridot from the Red Sea; Bohemian and Hungarian opal, garnet, and amethyst. Relatively few pearls have survived in good condition after being buried for approximately 350 years.

Gold and diamond finger ring: 16th – 17th century-Museum of London

Navvy-Ford Max Brown-wiki

1912 The Cheapside Hoard, “Stony Jack” & the Navvies

The Cheapside Hoard was discovered by a ‘Navvy‘, one of many workmen often hired for railroad work and excavations at the time. The discovery was made in a cellar at 30–32 Cheapside in London, on the corner with Friday Street. One of the navigators armed only with a pickaxe uncovered a wooden box containing more than 400 pieces of Elizabethan and Jacobean jewellery. The treasures include rings, brooches and chains, with bright coloured gemstones and enamelled gold settings, together with toadstones, cameos, scent bottles, fan holders, crystal tankards and a salt cellar.

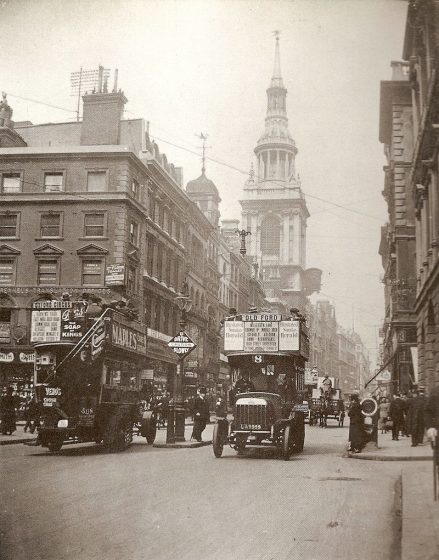

Cheapside 1909 photo: Public Domain

In a brick-lined cellar under a chalk floor, the workman cleared debris and saw a decayed wooden box containing a hidden treasure of several hundred gleaming jewels.

The gems spilt onto the muddy floor and experienced their first light of day after nearly 300 years of concealment. The treasure buried in the cellar would have been lost to history were it not for a quirk of fate. An antiquities trader and pawnbroker named George Fabian Lawrence established a shrewd arrangement with demolition workers. “Stony Jack,” as he was known, would pay them in cash or pints of beer for interesting finds. “I taught them that every scrap of metal, pottery, glass, or leather that has been lying under London may have a story to tell the archaeologist, and is worth saving,” Lawrence told the Daily Herald in 1937, toward the end of his life. The discovery on June 18, 1912, at the intersection of Cheapside and Friday streets, was to become Lawrence’s most significant procurement.

Over the ensuing weeks, parcels and handkerchiefs of jewellery from the Cheapside Hoard showed up at his office, and an astonishing collection began to accumulate. This treasure of mostly Elizabethan and Jacobean jewellery eventually constituted almost 500 pieces.

Stony Jack Lawrence-photo: Smithsonian Museum

Lawrence’s success in antiquities and his connections with the crews paid off in 1912 when he became the inspector of excavations for the newly established London Museum.

The items in the Cheapside Hoard include a Byzantine gemstone cameo, a cameo of Queen Elizabeth I, an emerald parrot, and some fake gemstones made of carved and dyed quartz. A small red intaglio stone seal bears the arms of William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford, dating the burial of the hoard between his ennoblement in November 1640 and the Great Fire of London in September 1666, which destroyed the buildings above. Most of the gold is the “Paris touch” standard of 19.2 carats (80 percent pure). Most of “the hoard” is now in the Museum of London, with some items held by the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

https://www.gia.edu/gems-gemology/fa13-cheapside-hoard-weldon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheapside_Hoard